Accessibility in UK retail mobile apps

I have slowly been getting more interested in the accessibility of mobile apps. This has partly been driven by finding out just how many options there are to improve accessibility of apps, both for users and developers, and realising that many developers don’t know they exist. And, even when they are known about, there isn’t always much information about how to use them well.

To make this a bit more robust, I installed a bunch of UK shopping apps just to see what the current state of accessibility was and the results were… disappointing.

In fact, the issues I found were bad enough and widespread enough that I decided to write a series of posts going over some of the issues and explaining methods to improve them.

Testing details

The following is based on an iPhone 15 running iOS 18.5. Despite being an Android user myself, I have far more experience developing for iOS. I want to approach this with the goal of improving things and not just dunking on apps with shortcomings. For iOS I can give more concrete advice about how to make things better.

I also limited myself to just browsing around the app. I did not create an account, I did not attempt to purchase.

Summary of common issues

Before I get into the weeds of specific problems in specific apps (and hopefully how to improve them), I have a summary of common issues that were present in most apps.

Lack of large text support

Users can change the size of the text on their device, and many do. In fact this is probably the most used accessibility feature with somewhere between 20% and 30% of users selecting a larger text size.

For iOS developers, this feature is called dynamic type. For many system controls it is enabled automatically.

For custom controls, it is is enabled automatically in SwiftUI (but can be disabled), but has to be explicitly enabled in UIKit.

Cross platform frameworks vary. Xamarin did not support it and getting to work was tricky. MAUI supports it by default.

For the apps I tried:

- Several had no support at all for large text. They are likely using UIKit for everything, or a wrapped web view.

- Most had sporadic support for large text. The specific places suggest it was accidental. This could be some system controls without a custom font, or SwiftUI controls embedded in UIKit.

- A few had broken support - some screens mostly unusable. Likely using SwiftUI with automatic support but with no testing.

Voiceover

iOS has a built-in screen reader, VoiceOver. Standard controls are well supported automatically, and simple layouts should just work. Any even slightly complex app will require additional work to make sure things have the correct labels, ordering is sensible, and element grouping makes sense.

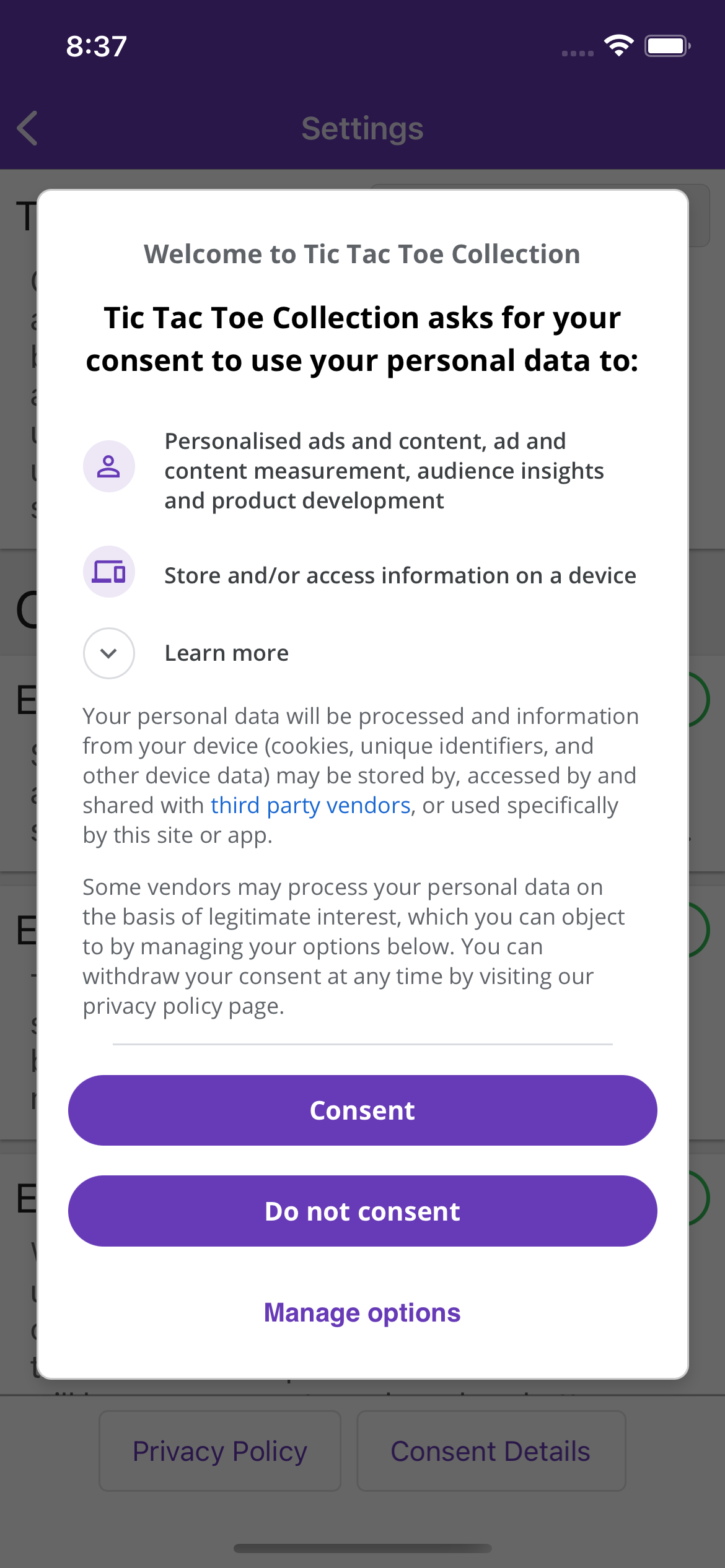

Sheets and popups

Several apps had problems with modal displays that were not actually modal. That is, a full screen popup that still let you interact with UI in the background (that you couldn’t even see).

Worst of all, most of these examples were during the app onboarding making it the first thing a user would interact with.

Most also had smaller popups or menus that didn’t focus properly when they appeared.

Ordering

A key feature of VoiceOver is sequential navigation. You can always navigate to “next” and “previous” elements under the assumption that user may not be able to see the screen at all. For this to work the content has to be sensible order.

Simple cases will just work, but grid layouts may not work automatically, and overlapping elements will almost certainly have some undesirable ordering.

Every app had at least one screen that handled this very badly. They also had screens that were just about usable but not pleasant.

Grouping

By default every element that has text or is interactive will be treated as a separate element to VoiceOver. This isn’t always desirable.

One common example is multiple text elements (often with different formatting) intended to be read in one go are split up. Every app had at least one example of this, with some handling badly in many places.

Another one that is a bit more subjective is handling long lists. Imagine a list (or commonly a grid) of products with a title, a price, a brand name, a star rating, a “like” button, and an image. If each of those is an individual element, it takes very many “next” swipes to get through items. Nearly every app had this problem.

Labels

Text content will be labeled automatically, but images need to have labels added manually. If one isn’t specified, iOS will often read out the file name of the image which is often nonsensical.

Every app had at least one example of this. Most also had at least one label that obviously added but not useful (for example an image just labeled “Promotional banner”).

Other interaction methods

As well as VoiceOver, there are a few more ways to interact with an app that largely depend on the same works as above - good naming, ordering, and grouping.

Switch control

With switch control interaction can be limited to a small number of switches. This is not something I have tried very much, but it fails without good item ordering.

Voice control

Select elements by saying “Tap X”. Unintuitively this is quite resilient to poor element naming since you can see* the labels and it has built-in support for disambiguation. What does cause problems is insufficient grouping. Most of the apps had areas with too many individual items in close proximity that were hard to select.

* I used it while I could see. This can be combined with VoiceOver by a user who cannot see. In which case all the difficulties of VoiceOver also apply.

Other minor points

Invert

iOS has a smart invert option that inverts all the colors. Developers should annotate photographic imagery to be not inverted, but most of the apps did not.

Bold

Users can choose to make all text bold. This will be supported automatically if using system fonts, but not if using custom fonts. None of the apps supported this properly, with only a few controls (likely using system fonts) appearing bold.